A cool pocket climate around the snout of a glacier could help researchers predict how forests will respond to fast climate change, according to the authors of a new 166-year case study of a rapidly advancing and retreating glacier in Alaska.

Hiking in snowy mountains or trudging by a snowbank on the sidewalk, you may have felt a cool pocket of air near a pile of snow. Trees near glaciers experience that same effect and it can slow their growth. Trees record the history of cooling in their yearly growth rings, as the new study in AGU’s Geophysical Research Letters reports.

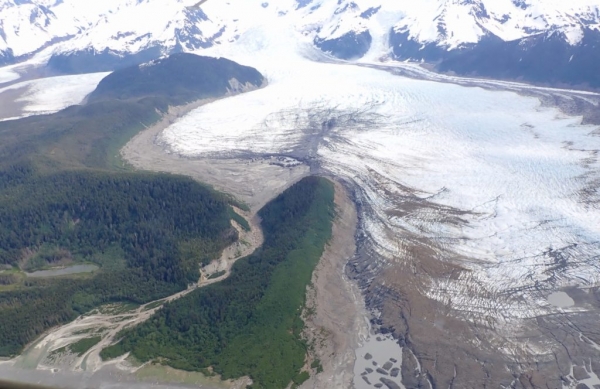

Tree ring growth depends on many factors, including temperature. For many species, cooler, drier conditions lead to slower growth and smaller or denser rings. The study, led by ecologist Ben Gaglioti, documents this relationship on the La Perouse glacier and the surrounding Glacier Bay National Forest in an unprecedented up close and personal view of past glacial microclimates.

From historical accounts, tree cores and aerial imagery, the team knew the glacier rapidly advanced hundreds of meters during the late 1800s, ping-ponged during the early 1900s, and began retreating around 1950. The next step was to check if the trees recorded microclimate shifts during those periods.

Read more at American Geophysical Union

Image: The trees around La Perouse glacier, in Glacier Bay National Forest, recorded microclimate changes as the glacier advanced and retreated. A new study in AGU’s Geophysical Research Letters reports on how scientists can use those records to predict how near-glacier ecosystems will respond to future climate change. (Photo Credit: B. Gaglioti)