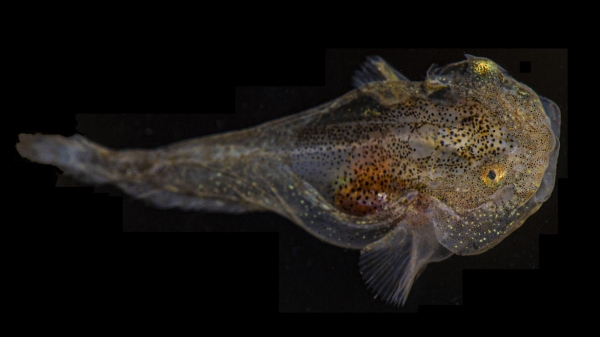

In 2019, Museum researchers diving in the icy waters surrounding Greenland discovered something unexpected: a small fish glowing in green and red. This glow, or biofluorescence, is an unusual property for fish in the Arctic, where there are prolonged periods of darkness. The tiny snailfish they identified remains the only polar fish reported to biofluoresce. Now, the researchers have uncovered something else surprising about this otherwise unassuming fish: it contains soaring levels of antifreeze proteins.

“Similar to how antifreeze in your car keeps the water in your radiator from freezing in cold temperatures, some animals have evolved amazing machinery that prevent them from freezing, such as antifreeze proteins, which prevent ice crystals from forming,” said David Gruber, a research associate at the Museum and a distinguished biology professor at Baruch College, City University of New York, and a co-author of the study, published today in the journal Evolutionary Bioinformatics. “We already knew that this tiny snailfish, which lives in extremely cold waters, produced antifreeze proteins, but we didn’t realize just how chock-full of those proteins it is—and the amount of effort it was putting into making these proteins.”

Unlike some species of reptiles and insects, fishes cannot survive even partial freezing of their body fluids, so they depend on antifreeze proteins, made primarily in the liver, to prevent the formation of large ice grains inside their cells and body fluids. The ability of fishes to make these specialized proteins was discovered nearly 50 years ago, but the genes of the fish examined in this study, the juvenile variegated snailfish (Liparis gibbus) have the highest expression of antifreeze proteins ever observed.

Read more at American Museum of Natural History

Image: Liparis Gibbus (white light). Credit: © John Sparks and David Gruber