Rising air temperatures due to global warming melt glaciers and polar ice caps. Seemingly paradoxically, snow cover in some areas in northern Eurasia has increased over the past decades. However, snow is a form of water; global warming increases the quantity of moisture in the atmosphere, and thus the quantity and likelihood of rain and snow. Understanding where exactly the moisture comes from, how it is produced and how it is transported south is relevant for better predictions of extreme weather and the evolution of the climate.

Hokkaido University environmental scientist Tomonori Sato and his team developed a new tagged moisture transport model that relies on the “Japanese 55-year reanalysis dataset”, a painstaking reanalysis of world-wide historical weather data over the span of the past 55 years. The group used this material to keep their model calibrated over much longer distances than hitherto possible and were thus able to shed light onto the mechanism of the moisture transport in particular over the vast landmasses of Siberia.

A standard technique to analyse moisture transport is the “tagged moisture transport model”. This is a computer modelling technique that tracks where hypothetical chunks of atmospheric moisture form, how they are moved around, and where they precipitate due to the local climatic conditions. But the computer models become more and more inaccurate as the distance to the ocean increases. In particular, this makes quantitative predictions difficult. Thus, these methods have not been able to satisfyingly explain the snowfall in northern Eurasia.

Read more at: Hokkaido University

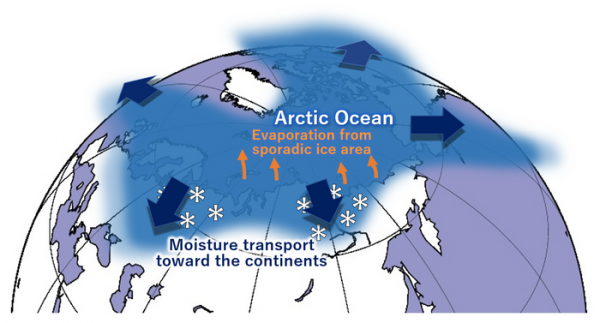

An increasingly warm and ice-free Arctic Ocean has, in recent decades, led to more moisture in higher latitudes. This moisture is transported south by cyclonic weather systems where it precipitates as snow, influencing the global hydrological cycle and many terrestrial systems that depend on it (Illustration: Tomonori Sato). (Photo Credit: Tomonori Sato)