As increased warming in Antarctica causes glaciers to retreat and shed their increasingly-unstable shelves, towering walls of ice are left looming high above the sea. But how tall these rugged cliffs actually grow before they come crashing down has been a question for glacial scientists—and one that has important implications for sea-level rise.

“There’s a theory out there that says ice is only so strong, so it can only ever reach a certain height before it breaks apart,” says WHOI assistant scientist Catherine Walker, who studies the dynamics of ice on Earth and in space. “In the case of ice cliffs, the general assumption has been that a cliff can only grow to roughly one-hundred meters—just slightly higher than the Statue of Liberty—before it collapses under its own weight and falls into the ocean.”

The theory, it turns out, stems from research that University of Michigan professor Jeremy Bassis and Walker conducted a decade ago. They had come up with some relatively straightforward calculations and combined those with estimated heights of ice cliffs that had been observed in existing ice shelves to settle on the 100-meter figure.

Read more at: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute

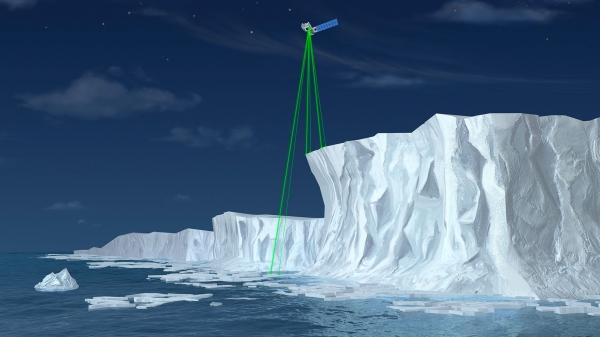

Illustration of NASA’s Ice, Cloud and land Elevation Satellite-2 (ICESat-2). (Photo Credit: NASA)