Doctors and public health experts agree that breathing fine particulate matter (PM2.5) can be harmful to human health. The airborne particles—thirty times smaller than the width of human hair—can pass easily into the lungs and bloodstream, where they can increase a person’s risk of dying from heart disease, stroke, lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and lower respiratory infections.

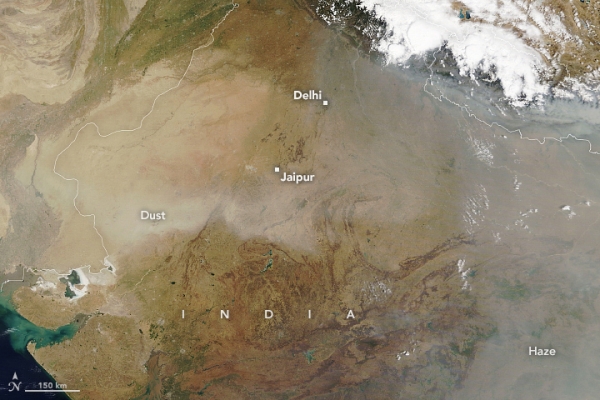

However, current estimates of the total number of premature deaths linked to PM2.5 range widely, from 3 to 9 million people each year. And there has long been uncertainty about the proportion of these deaths that are due to naturally occurring windblown dust versus human-caused (or anthropogenic) pollution, which comes from factories, transportation, power plants, cookstoves, crop fires, and other sources.

Research led by a team of atmospheric scientists based at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center indicates that the health burden associated with PM2.5 is somewhat lower than previous estimates suggest—and sheds light on the role of dust. The researchers—including Hongbin Yu and Alexander Yang—calculated the global health effects of PM2.5 by analyzing exposure over an extended period of time using a NASA atmospheric modeling system integrated with medical data from the Univeristy of Washington’s Global Burden of Disease Study.

Read more at: NASA Earth Observatory

Photo Credit: Lauren Dauphin