The North Pacific “Garbage Patch” aggregates an abundance of floating sea creatures, as well as the plastic waste it has become infamous for, according to a study published in PLOS Biology and co-authored by oceanographers in the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST).

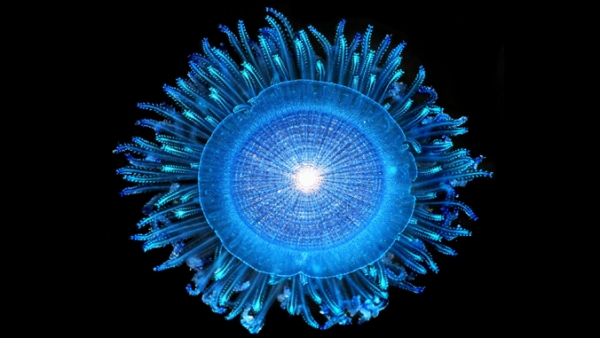

Marine surface-dwelling organisms, such as jellies, snails, barnacles and crustaceans, are a critical ecological link between diverse ecosystems, the study authors wrote, but very little is known about where these organisms are found. Plastic pollution provides a clue: the oceanographic forces that concentrate buoyant man-made waste and pollutants in “garbage patches,” may also aggregate floating life.

There are five main oceanic gyres—vortexes of water where multiple ocean currents meet—of which the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre is the largest. It is also known as the North Pacific “Garbage Patch,” because converging ocean currents have concentrated large amounts of plastic waste there.

The researchers leveraged an 80-day, long-distance swim by Benoît Lecomte through the gyre in 2019, dubbed The Vortex Swim. To investigate these floating lifeforms, the sailing crew accompanying the expedition collected samples of surface sea creatures and plastic waste. The expedition’s route was planned using computer simulations developed by SOEST oceanographers, Nikolai Maximenko and Jan Hafner, which simulate ocean surface currents to predict areas with high concentrations of marine debris.

Read more at University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

Image: Blue button jellies float on the surface. (Photo credit: Denis Riek via University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa)