The seafloor is home to around one-third of all the microorganisms on the Earth and is inhabited even at a depth of several kilometers. Only when it becomes too hot does the abundance of microorganisms appear to decline. But how, and from what, do microorganisms in the deep seafloor live? How do their metabolic cycles work and how do the individual members of these buried communities interact? Researchers have now been able to demonstrate in laboratory cultures how small, liquid components of crude oil are broken down through a new mechanism by a group of microorganisms called archaea.

Microbial communities are especially active near hydrothermal seeps like those in the Guaymas Basin in the Gulf of California. The team of researchers has been working on understanding these communities for many years. Organic material deposited in the Guaymas Basin is cooked by heat sources from within the Earth, which breaks it down into crude oil and natural gas. Their components provide the primary source of energy for microorganisms in an otherwise hostile environment. In their latest study, the researchers have demonstrated that archaea use a previously unknown mechanism to degrade liquid petroleum alkanes at high temperatures without the presence of oxygen.

Read more at MARUM - Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen

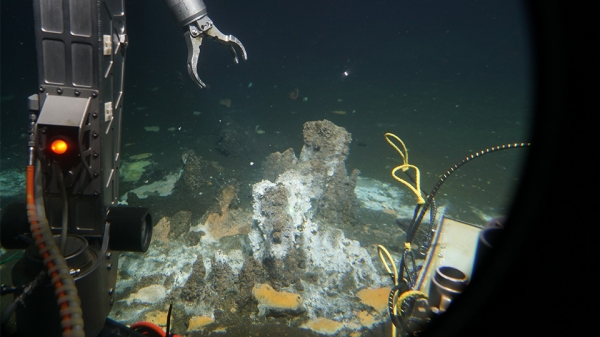

Image: In the spotlight of the U.S. deep-sea submersible ALVIN, a small reddish-brown vent massif can be seen on the seafloor of the Guaymas Basin. This formation is surrounded by abundant hydrothermally heated oil-rich sediments covered by white and orange bacterial mats. The core from which the Candidatus Alkanophaga archaea ultimately originated was collected by the team of the manned deep-sea submersible. (Photo: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Photo: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution via MARUM.)