Surface ice in Greenland has been melting at an increasing rate in recent decades, while the trend in Antarctica has moved in the opposite direction, according to researchers at the University of California, Irvine and Utrecht University in the Netherlands.

For a paper published recently in the American Geophysical Union journal Geophysical Research Letters, the scientists studied the role of Foehn and katabatic winds, downslope gusts that bring warm, dry air into contact with the tops of glaciers. They said that melting of the Greenland ice sheet related to these winds has gone up by more than 10 percent in the past 20 years; the impact of the winds on the Antarctic ice sheet has decreased by 32 percent.

“We used regional climate model simulations to study ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica, and the results showed that downslope winds are responsible for a significant amount of surface melt of the ice sheets in both regions,” said co-author Charlie Zender, UCI professor of Earth system science. “Surface melt leads to runoff and ice shelf hydrofracture that increase freshwater flow to oceans – causing sea level rise.”

While the impact of the winds is substantial, he said, the distinct behaviors of global warming in the Northern and Southern hemispheres are causing contrasting outcomes in the regions.

Read more at University of California - Irvine

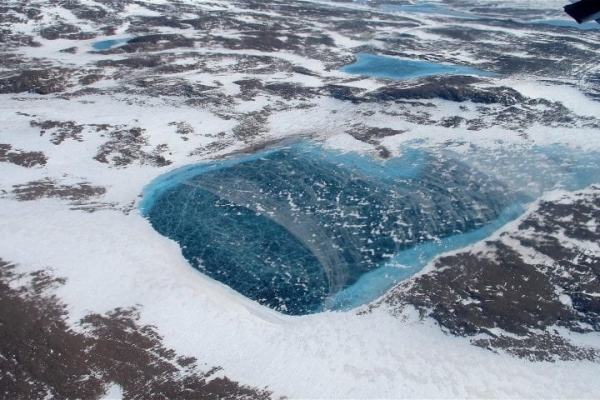

Image: Greenland is dotted with frozen meltwater lakes such as the one above, photographed during a NASA expedition in 2012. UCI Earth system scientists led a study into the role of warm, dry, downslope winds in accelerating thawing of the Greenland ice sheet. As part of the same project, the researchers found a contrasting outcome at the other end of the globe: less wind-driven melting in Antarctica. (Credit: NASA Operation IceBridge)