As a renewable resource, biomass presents an appealing alternative to fossil fuels for energy production. Burning plants, however, is not a completely clean process; it produces emissions that vary depending on the species used, the combustion conditions, and the air pollution controls.

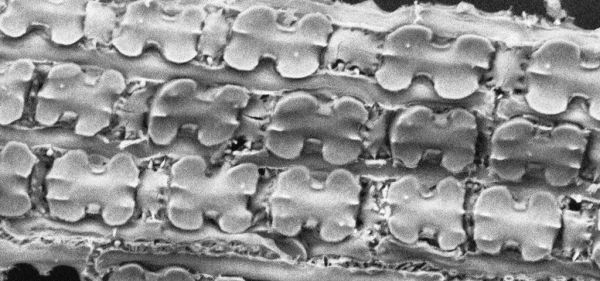

To understand one component of these emissions, an international, multidisciplinary team led by University of Pennsylvania mineralogists used highly sensitive microscopy to study phytoliths, small deposits of minerals containing silicon or calcium present in certain plants. These chemical elements are absorbed from the soil along with other nutrients. The phytoliths lend plants strength and structure and are common in some plant families commonly used for biofuel, such as grasses.

Reporting in Industrial Crops & Products, the researchers found that phytoliths remain after plants are burned in a biofuel combustion facility but in particle sizes large enough that they likely don’t pose a health risk. But because phytoliths can reduce the efficiency of energy conversion, power plants must factor them into their operations, the team notes. On the other hand, the phytolith-containing ash resulting from combustion could be sold for use in cement production or as fertilizer.

Continue reading at University of Pennsylvania

Image via University of Pennsylvania