When we experience a new event, our brain records a memory of not only what happened, but also the context, including the time and location of the event. A new study from MIT neuroscientists sheds light on how the timing of a memory is encoded in the hippocampus, and suggests that time and space are encoded separately.

In a study of mice, the researchers identified a hippocampal circuit that the animals used to store information about the timing of when they should turn left or right in a maze. When this circuit was blocked, the mice were unable to remember which way they were supposed to turn next. However, disrupting the circuit did not appear to impair their memory of where they were in space.

The findings add to a growing body of evidence suggesting that when we form new memories, different populations of neurons in the brain encode time and place information, the researchers say.

“There is an emerging view that ‘place cells’ and ‘time cells’ organize memories by mapping information onto the hippocampus. This spatial and temporal context serves as a scaffold that allows us to build our own personal timeline of memories,” says Chris MacDonald, a research scientist at MIT’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory and the lead author of the study.

Read more at Massachusetts Institute of Technology

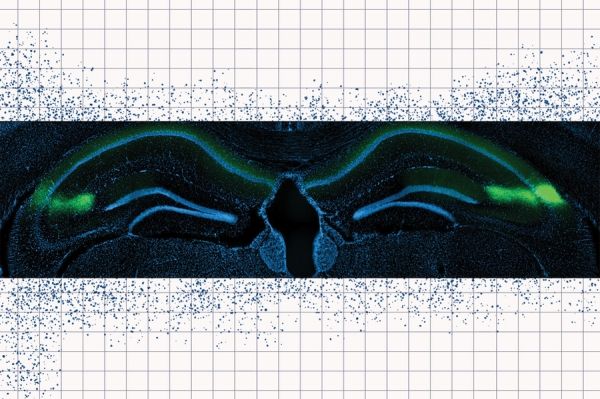

Image: MIT neuroscientists have found that pyramidal cells (green) in the CA2 region of the hippocampus are responsible for storing critical timing information. Credits: The Tonegawa Lab, edited by MIT News