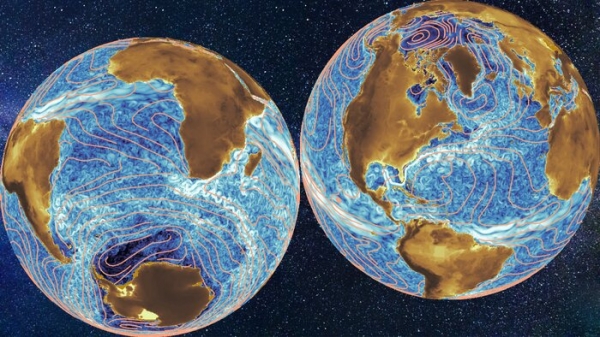

For the first time University of Rochester researchers have quantified the energy of ocean currents larger than 1,000 kilometers. In the process, they and their collaborators have discovered that the most energetic is the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, some 9,000 kilometers in diameter.

The team, led by Hussein Aluie, associate professor of mechanical engineering, used the same coarse-graining technique developed by his lab to previously document energy transfer at the other end of the scale, during the “eddy-killing” that occurs when wind interacts with temporary, circular currents of water less than 260 kilometers in size.

These new results, reported in Nature Communications, show how the coarse-graining technique can provide a new window for understanding oceanic circulation in all its multiscale complexity, says lead author Benjamin Storer, a research associate in Aluie’s Turbulence and Complex Flow Group. This gives researchers an opportunity to better understand how ocean currents function as a key moderator of the Earth’s climate system.

The team also includes researchers from the University of Rome Tor Vergata, University of Liverpool, and Princeton University.

Read more at University of Rochester

Image: This illustration by Benjamin Storer shows oceanic currents from satellite data overlaid with large scale circulation currents (gold lines) which can be extracted with a coarse graining technique developed in the lab of Hussein Aluie. Note the most energetic of these currents— the Antarctic Circumpolar Current—at lower left. (Credit: Benjamin Storer (Aluie lab at University Rochester))