When organisms pass their genes on to future generations, they include more than the code spelled out in DNA. Some also pass along chemical markers that instruct cells how to use that code. The passage of these markers to future generations is known as epigenetic inheritance. It’s particularly common in plants. So, significant findings here may have implications for agriculture, food supplies, and the environment.

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professors and HHMI Investigators Rob Martienssen and Leemor Joshua-Tor have been researching how plants pass along the markers that keep transposons inactive. Transposons are also known as jumping genes. When switched on, they can move around and disrupt other genes. To silence them and protect the genome, cells add regulatory marks to specific DNA sites. This process is called methylation.

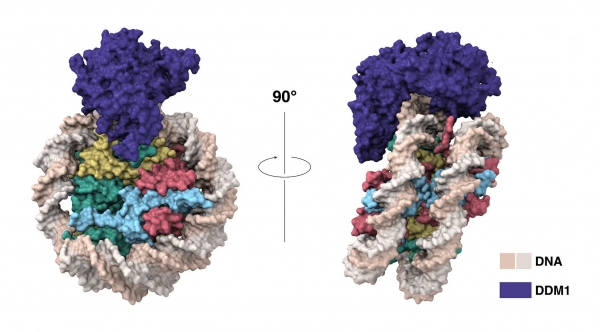

Martienssen and Joshua-Tor have now shown how protein DDM1 makes way for the enzyme that places these marks on new DNA strands. Plant cells need DDM1 because their DNA is tightly packaged. To keep their genomes compact and orderly, cells wrap their DNA around packing proteins called histones. “But that blocks access to the DNA for all sorts of important enzymes,” Martienssen explains. Before methylation can occur, “you have to remove or slide the histones out of the way.”

Read more at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Illustration: This cartoon model illustrates, for the first time, where and how the DDM1 protein (purple) grips onto DNA (beige) during cell division. Credit: Joshua-Tor lab/Cryo-EM Facility/Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory