Snow is one of the most contradictory cues we have for understanding climate change.

As in many recent winters, the lack of snowfall in December seemed to preview our global warming future, with peaks from Oregon to New Hampshire more brown than white and the American Southwest facing a severe snow drought.

On the other hand, January has brought some heavy snow to New England, and record blizzards in early 2023 buried California mountain communities, replenished parched reservoirs, and dropped 11 feet of snow on northern Arizona, defying our conceptions of life on a warming planet.

Similarly, scientific data from ground observations, satellites, and climate models do not agree on whether global warming is consistently chipping away at the snowpacks that accumulate in high-elevation mountains and provide water when they melt in spring, complicating efforts to manage the water scarcity that would result for many population centers.

Read more at: Dartmouth College

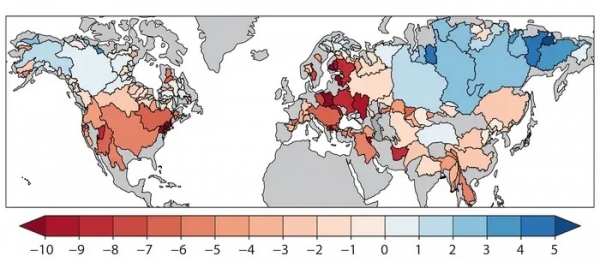

Effect of human-driven global warming on spring snowpacks in Northern Hemisphere watersheds from 1981-2020 by percentage of change per decade. Red indicates a decrease and blue indicates an increase. Snowpacks in many far-north watersheds increased as climate change led to more precipitation that fell as snow. But the lower-latitude watersheds that provide water and economic benefits to northern population centers experienced the greatest losses. (Photo Credit: Justin Mankin and Alex Gottlieb/Dartmouth)