It’s common knowledge that, through the process of natural selection, organisms adapt to their environments. But what happens when there are no barriers to gene flow and organisms are free-floating between extremely variable environmental conditions?

A new study by UConn researchers seeks to tease out some of the myriad pressures that drive adaptation in small, widely dispersed marine animals called copepods — small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat — to understand how these animals may cope with an increasingly warming climate.

“We often assume that species adapt in fairly predictable patterns,” says Matthew Sasaki a doctoral student in the UConn’s Department of Marine Sciences, who is based in the lab of Professor Hans Dam. “However, what we know about these patterns is mainly from animals living on land rather than animals living in ocean currents.”

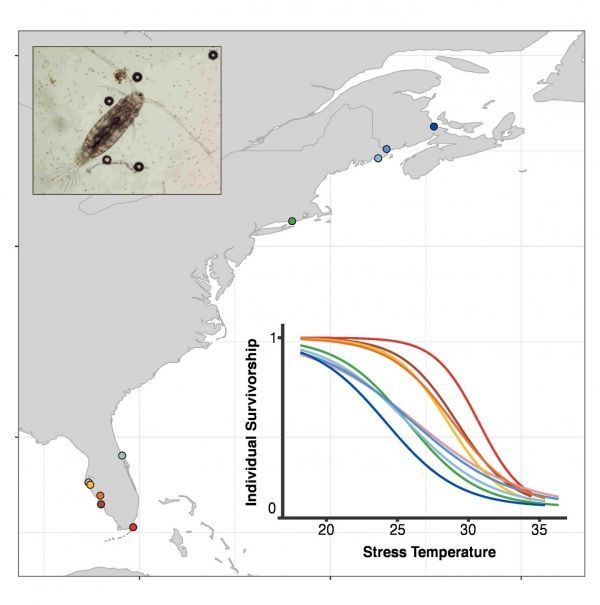

Based on what we know about organisms on land, the expectation is that populations of copepods in warmer environments, like Florida, would be more resistant to higher temperatures whereas populations in colder environments like Canada would have lower thermal tolerance.

Read more at University of Connecticut

Image: Copepod sample range. (Credit: Matthew Sasaki)